Ever heard of a software project that missed the deadline, was full of bugs, and ended up costing way more than estimated?

There is a reason why so many software projects go over budget, are delivered late, or fail to satisfy the end-user needs—and it’s probably not what you think.

Civil Engineering

Many development teams approach software engineering with practices borrowed from civil engineering.

It might surprise you, but these civil engineering practices were already developed in the 19th century—before 1900.

This essentially means that many software products are being built with engineering practices that are over 100 years old!

We didn’t have software back then—actually, we didn’t even have computers. At the end of the 19th century, we were still busy getting used to lightbulbs. 💡

Civil engineering practices work for building bridges and skyscrapers. Here, it makes sense to put a lot of time and effort into planning, creating blueprints, and even conducting expensive formal sing-offs before starting the next development stage.

And why is that?

In civil engineering, mistakes can turn out to be really, really expensive.

When building a house, it makes sense to start with the foundation, then stack up one story after another, and finally install all the electronics and plumbing.

What works great for buildings fails for software.

Software is, by nature, fundamentally different from things we can build.

Once we build a house, changing it becomes extremely hard, if not impossible.

Software, on the other hand, is … well, soft. Things change all the time. It’s more like a living thing.

Requirements, for instance, will change over the course of a software project. It’s impossible to nail down all the software requirements upfront and get them right.

Building SOFTware is HARD

Trying to build software like buildings is a fool’s errand.

And that’s why I like to compare software to plants.

We can’t just build a tree!

We have to start by planting a seedling. We have to water it. And if we don’t take care of it, it will die off or grow wild. So we have to prune it from time to time.

Over time, the seedling will grow into a sprout, then a small tree, and eventually, it will turn into a mighty oak.

We cannot build a house without a foundation or live or work in a building until it’s completed. A tree, on the other hand, can de-carbonize the air or provide shadow long before it turns into a mighty oak.

With software, it’s similar. Software deteriorates over time if we don’t take action. We have to maintain it to keep it alive.

We have to update open-source libraries to patch security holes. As we add features and the complexity grows, we must simplify and clean our codebase (a.k.a. refactoring). And we have to change features based on end-user feedback and evolving legal requirements.

If we fail to do that, the software product will die.

A software product that does not solve the end-user’s problem will not be used and will not generate revenue to cover the development and maintenance costs.

If the software is not updated regularly, it might be kicked out of app stores or shut down by a legal entity.

And if the codebase is not continuously refactored, development speed for adding features or fixing issues will slow down (meaning it becomes increasingly expensive). Eventually, the developers will ask for a rewrite or leave the company. That’s when the product’s development will grind to a halt.

Creating software requires a different approach.

The codebase needs to be adjustable, and the development approach itself must acknowledge that the software will have to change over time.

The Agile movement in the 90s acknowledged that by introducing new principles like Emergent Design and development practices like Test-first Programming. And the DevOps movement in the 2010s improved on it with practices that automate repetitive and error-prone operational tasks.

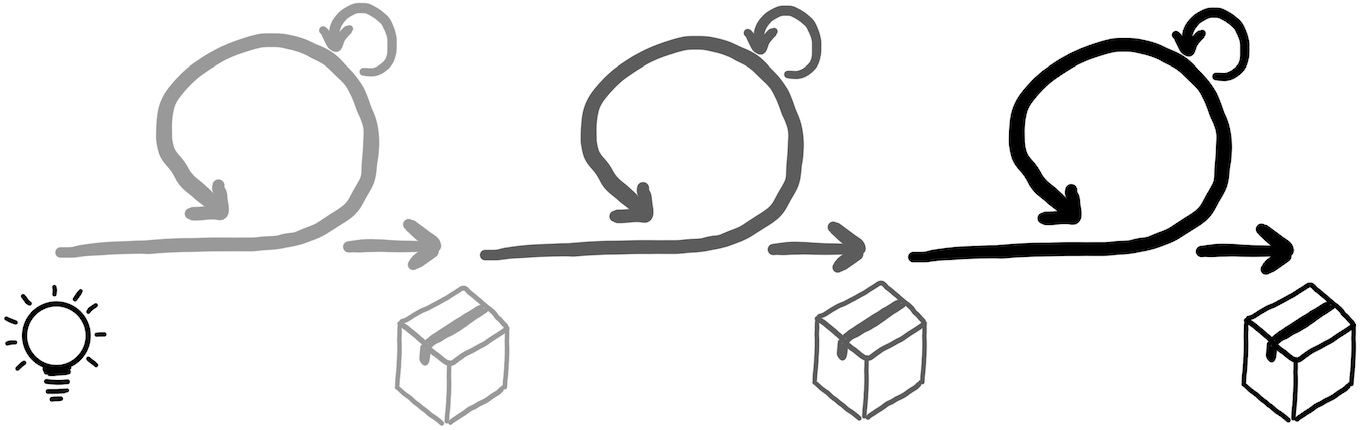

With Agile and DevOps, we develop software products incrementally.

Usually, we start with the most important features first and keep less important details for later. That ensures that there will be something of value to end-users from very early on during the development process.

Like the seedling that can already de-carbonize the air or that young tree that can already provide shadow.

Every product increment can be presented to our end-users. Short feedback cycles ultimately result in higher quality and reduce the risk of developing the wrong thing.

Over time, the software will grow into a sophisticated solution with all the essential features and perhaps even some nice-to-have features that are not needed every day.

Unfortunately, many companies still haven’t adopted Agile or DevOps principles and practices to this day. Some pretend to be Agile, but when you look closely, you will notice they are just faking it. Their projects fail as before. They go over budget, are late, and the quality is poor. But this is a different story.

What do you think about the plant metaphor I use for software? Send me a message and let me know – I read all emails!

See you around,

David